By Nathan Ahlgrim, Neuroscience, ‘14

Edited by Amielle Moreno, Neuroscience ‘12

Graduate school can be many things to many people, but one thing it is decidedly not is easy. It’s a long slog from admissions to defense, and each one of us needs the promise of life post-Ph.D. to get us through the hard times. The post-Ph.D. life feels closer with each milestone reached, with each success achieved. Traditionally, measuring academic success was straightforward. Have you published? If so, how many papers, and where? Positive answers to those questions set graduate students up for success on the path towards the professoriate. But newly minted Ph.D.’s are leaving academia in increasing numbers, and intra-Ph.D. life needs to be bearable, too.

Success in graduate school can no longer be placed on the resulting job and career path since so many do not even hold academia as a goal. For those students, and even the ones with dreams of a professorship just trying to get through a 6-year Ph.D., success needs to be defined within the program. The people in academia are changing, and the traditional markers of success are not the be-all and end-all in many labs. Even so, praise for other achievements, be they in education, outreach, professional development, or soft skills, is rarely explicit in the lab. Graduate students are almost universally successful. They were, after all, invited into their program. For the purposes of motivation, mental health, and yes, even the career path, graduate students need to be recognized for the successful people they become as a graduate student, not only for the successful scientist.

It does not take much digging to realize the single-minded emphasis on the dissertation defense at the exclusion of all else is misguided. The way we think about success in graduate school doesn’t even fit the criteria of intelligent goal setting. S.M.A.R.T. goals, those that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound, are favored by coaches, dieticians, and bosses. The goal of “get my Ph.D.” fails to meet almost every criteria. It does not lay out a Specific task, there are few benchmarks (Measurable), and dissertations only end when your committee gives the ok (Time-bound). At times, it fails to even feel achievable or relevant.

Graduate school, in effect, is set up like a diet doomed to fail. If you only consider yourself a success once you achieve a Chris Pratt Parks and RecàGuardians of the Galaxy transformation, I can confidently say you won’t make it. The struggles are too long, the progress is too gradual, and the sacrifices are too ubiquitous. Sound familiar? The only way to keep going is to celebrate, or at the very least acknowledge, the successes along the way.

Graduate programs have different strategies for paying lip service to intra-program success. Some award Master’s degrees, some make a big deal of qualifying exams. I was going to make the list longer, but honestly, I can’t think of a third example. Many students have a lab lunch celebrating those achievements, but by two o’clock everything is back to normal. Programs also offer awards for top-performing students, and every grad student can apply to external grants and succeed in funding ourselves. These avenues of success, by definition, are limited (with award rates hovering around 15% for NSF GRFP and 25% for NIH fellowships). They acknowledge the cream of the crop. Make no mistake, the best-of-the-best deserve to be recognized for their excellence, but graduate students are already an elite group. The rest of us (not that I’m bitter or anything) are successful in our own right. Those years of candidacy, when we do not have exams to ace, we may not have grants to apply for, and we don’t see an end to the countless hours in lab, need wins that are achievable by every well-performing graduate student. Yes, we are success stories just by getting into the program, but that status cannot sustain motivation through a 5+ year program.

Of course, my list of achievements is lacking one big factor: papers. Getting published always kicks off a round of celebration! A graduate student with an impressive publication record is a successful graduate student, even if their dissertation itself stalls. However, as much as we wish it were otherwise, the Science Gods do not mete out their blessings in a merit-based system. Hard work is only weakly correlated with high-impact publications, and that lack of control is a bigger problem than most people are willing to admit. Lack of control necessitates Ph.D. programs building in milestones and achievements that are not directly related to the impact factor of journals students publish in.

Image of unreasonable PI

The grad school struggle presents a collection of hurdles. These hurdles are more than stumbling blocks – they potentially block professional and personal progress. As many as 40% of graduate students experience some mental health crisis while in their program (Levecque et al., 2017; Evans et al., 2018). We know some of the root causes, both from the graduate student surveys and studies of depression in general. Stressful events you can influence or control are much less likely to lead to depression than uncontrollable ones (Stansfeld et al., 1999; Rubenstein et al., 2016). We know this, and yet the progress and quality of students are still measured largely by uncontrollable outcomes.

Laboratory culture, it must be said, is changing, even if the changes are often slow and invisible. Many advisors still only talk about the traditional academic successes, because it’s what they know. There is nothing wrong with that. However, many graduate students are then hesitant to be anything other than a carbon copy of their advisor because they fear the anger, disappointment, or shame they think it will trigger. Laura, one recent GDBBS student felt this fear as she steeled herself to tell her advisor she decided to leave the program with a Master’s. She knew that leaving the program to become an educator was the right decision for her, yet she dreaded the conversation. As Laura told me, “I felt like I was letting him down … It felt rude, like a judgment on his life that I don’t want for myself”. Her advisor was a scientist at heart, and turning her back on academia made her feel like she betrayed his mentorship.

Then the conversation happened. Laura’s advisor was shocked. But then, “he took a couple seconds, he realized I was serious, and he immediately opened up to it.” In fact, he took an active role in making sure she landed on her feet.

The surprising level of support is not unique to Laura. Kev, another student who recently left with a Master’s, noted his advisor’s swift change of heart. Although he was initially met with concern that he was making the wrong career decision, all Kev had to do was justify his choice. After that, his advisor “no longer pressed the matter.” Once Kev landed a job, even though it was not that prized tenure-track professorship at a tier-one research university, his advisor was “excited … and supportive throughout the transition.”

Both Kev and Laura entered one of the hardest conversations a student can have with his/her mentor. Both were met, surprisingly, by support and understanding. Yes, there was pushback, and yes, Laura told me “there were definitely times that it felt like a failure.” But the choice to leave was not a failure for either of them. These advisors ended up supporting their students because they realized their students were making a wise choice. More importantly, they realized Kev and Laura would be happier and more successful out of the program. If this is how advisors now feel, why should these reactions come as a surprise? A broader definition of success needs to permeate graduate students’ training, not only to ease their minds, but to encourage diverse skill sets.

Unfortunately, the change of heart within individual advisors has yet to make its way into programming. A negative result can still dash the hopes of an intra-degree success even when the student’s work was exemplary. With the dissertation and resulting job being the singular mark of success in grad students’ lives, we rob them of the ability to control their own destinies. Moreover, we imply other achievements are secondary, if important at all. Of course we will never be able to eradicate mental health problems, but this environment amplifies them unnecessarily. Yes, supportive student-advisor relationships and a healthy work-life balance protect against the strain (Evans et al., 2018). But the strongest armor seems to be a goal of academic career after graduation (Levecque et al., 2017). The goal of entering the professoriate is so protective because of the explicit support within Ph.D. programs, and by advisors. For those looking elsewhere, fighting against the disapproval and disappointment of the scientific community is yet another hurdle. Reframing and expanding success will reframe and shrink failure and helplessness.

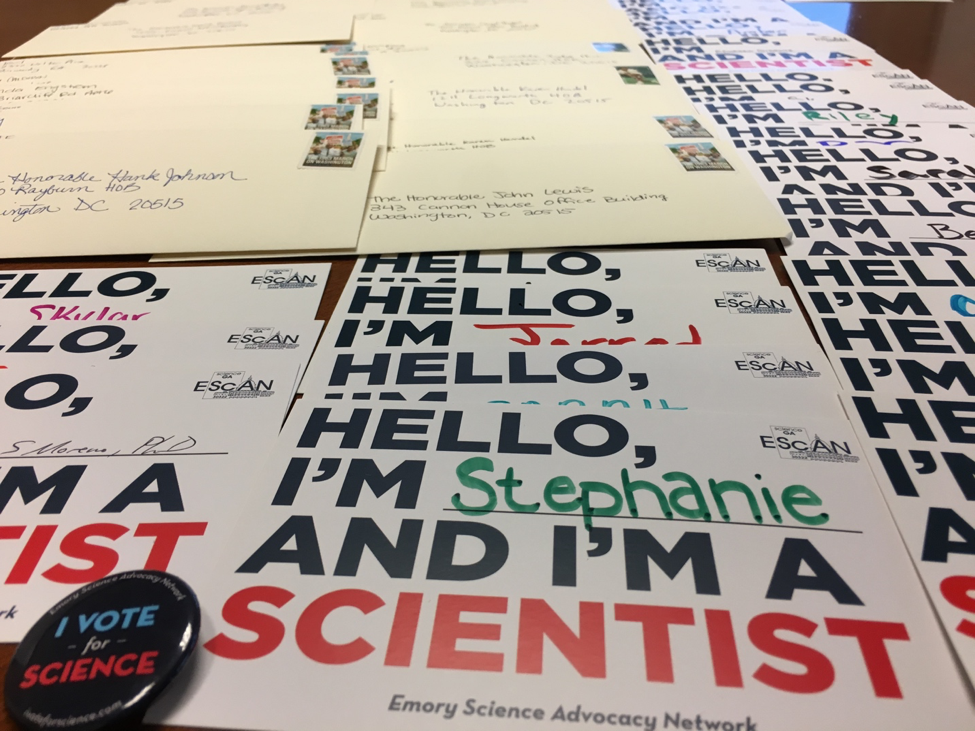

What does this look like, in the end? I already called out programs’ lip service, and it’s easy for new initiatives to fall into the same trap. I am not advocating for doling out participation trophies or gamifying the Ph.D. by unlocking achievements à la SuperBetter. Fostering a culture of success requires both a curriculum and a culture shift. Concrete feedback enables concrete successes. More importantly, so-called ‘soft skills’ need to be explicitly valued in the curriculum. Currently, any training or professional development for careers beyond the professoriate are done on the student’s own time. And yet, it is those trainings, volunteer efforts, and outreach events that make graduate students marketable for careers inside and outside of academia. The form it takes is not critical. Do I care if that means a student running a volunteer organization graduates with highest distinction, or a student leading museum tours on the weekend earns an extra certificate? No. The form of recognition is not as relevant as its existence.

Four years into my graduate career, I do have a few successes. I reached candidacy and published one paper. To many, that is the limit to the points I’ve racked up. Maybe I should subtract one because the paper has nothing to do with my dissertation work, and didn’t even involve my lab. Maybe I should subtract another one because I’m not honing my CV for an academic job. I have to convince myself I am successful for other reasons to keep myself motivated. Currently, the recognition from my teaching portfolio, my volunteer positions, and even my writing, is all internal. I am the one telling myself they are successes. But, being one of the 40-50% of graduate students who have faced mental health problems during/because of graduate school, it would certainly help if those successes were made official. It wouldn’t make graduate school easy. That’s not the point. It would, however, make graduate school verifiably worthwhile. For me as a scientist, and me as a person.

References

Evans TM, Bira L, Gastelum JB, Weiss LT, Vanderford NL (2018) Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature biotechnology 36:282.

Levecque K, Anseel F, De Beuckelaer A, Van der Heyden J, Gisle L (2017) Work organization and mental health problems in phd students. Research Policy 46:868-879.

Rubenstein LM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY (2016) Perceived control and depression: Forty years of research. In: Perceived control. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG (1999) Work characteristics predict psychiatric disorder: Prospective results from the whitehall ii study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 56:302-307.

I’d like to tell you my story about how I found myself on a project dedicated to helping families who have a child diagnosed with 3q29 deletion.