By: Sydney Sunna

As an English PhD student, Sarah Higinbotham began volunteering in 2008 as an educator at Phillips State Prison in response to her own uncle’s incarceration. Two years later she and a fellow graduate-student, Bill Taft, co-founded the organization Common Good Atlanta (CGA). Driven by the convictions that “higher education can restore dignity and reconnect people to their own humanity” and “communities are weakened when access to higher education is restricted on the basis of wealth, privilege, or class”, CGA has dedicated a decade to empowering people through correctional education. Today CGA offers more than 29 full-semester courses at four different correctional facilities, ranging from transitional to high-security penitentiaries. More than 50 faculty members from six universities, including those from Emory University, have taught courses in partnership with CGA.

Dr. Sober (Left) and Andrea Pack (Right)

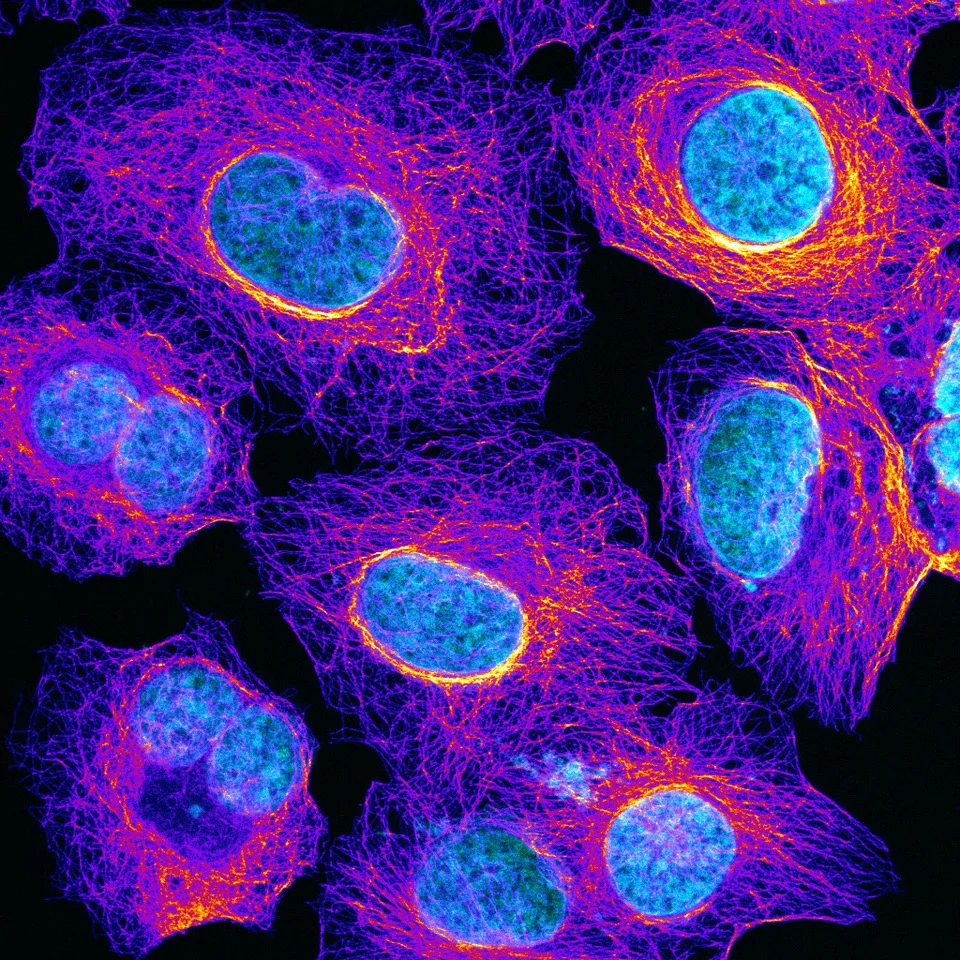

In the summer of 2016, Dr. Sober and Andrea Pack of the Neuroscience Program at Emory University partnered with CGA to provide a 6-week course on Systems-Neuroscience. The course curriculum now expands into other topics of interest such as Neuroethics and The Neurobiology of Disease. Andrea, who continues to play a role in the program prepares lesson-plans each year by devouring the literature underlying each subject, providing articles to the class, and hosting discussions and debates. Experiments and demonstrations punctuate the lectures. Following an introductory lecture to neurobiology, human and animal brains were brought in from Emory’s Brain Bank to compare the neuroanatomy of the different specimens. After a lesson on sensorimotory learning, the class period featured a demo in which zebra finches sang in response to hearing a melody from a mechanical watch alarm. When reflecting on this experience, Andrea explained “That was really special, … One student expressed ‘I haven’t seen an animal or a pet in twenty years’… and that is something that as a civilian, that’s free, we take advantage of, like seeing animals or playing with pets or just having a pet around”.

Since her involvement with CGA began years ago, Andrea has invested tirelessly in designing a curriculum that fulfills the interests and needs of her students. She emphasizes the value of creating a confidential environment for her students to participate in; enabling open and honest communication. When asked of the value she gains from educating inmates, Andrea shares that “[she’s] learning just as much as [her] students are…creating a safe and open place for discussion is a powerful way to bring together people of various backgrounds”. The neuroscience lectures are thoughtfully designed to be both salient and useful to her students. A couple months before her second-year teaching at Phillips State Prison, she began by providing a list of neurobiological diseases from which the students chose four to learn about in-depth. The favored four included post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), addiction, traumatic brain injury, and depression. Complimenting the lesson on PTSD, Andrea taught a course about the neuroscience behind and practice of meditation. Employing methodologies such as deliberate breathing, body-scanning, or taking a walk, this training sought to give students a resource in emotional regulation that they can use in their daily lives. The course taught this semester is on neuro-ethics. Originally, the course was designed as a discussion; the students would be assigned a reading and then the class would sit in a circle to discuss the ethics of the given topic. Topics range from a controversial head-transplant, the ethics of neuro-marketing, and a phenomenon known as neuro-hype in which popular media sources sensationalize scientific findings and influence public opinion. Andrea noticed that a few students would talk more frequently than others and she wanted to re-structure the class so that more people would have a chance to participate. The class then adopted a debate-style format in which students were assigned to be on the “pro” or “con” side of a given ethical issue. After the debate, the class would re-group as a whole to reflect on what each person actually thought about the topic. This flexible formatting of the courses is just one of many examples in which Andrea challenges herself to build a more inclusive environment for discussion. When asked about future lessons, she has some ideas about an assignment that would incorporate the artistic talents of her students. Each student received a lined or unlined journal according to their preference where they can express their thoughts and feelings on each subject. Students were assigned the task of creating a comic strip in response to topics covered in the neuroethics class. Andrea’s enthusiasm for designing a more engaging curriculum is infectious. When talking with Andrea, it quickly becomes clear that her students make just as much of a positive impact on her as her work does onto them.

The impact that CGA has on incarcerated people and the community is substantial. Since the organization formally began in 2010, more than 100 incarcerated men and women have completed a course, 4,000 hours of college classes have been taught, and the curriculum available ranges from Algebra to Nonviolent Political Theory (Common Good Atlanta [CGA], n.d.). As of May, 2019, CGA now provides courses to previously incarcerated people including a free dinner, free tuition, and free books and supplies to each student. Upon completion of the coursework, the students earn six transferrable academic credits from Bard college. Currently, the neuroscience program is the only scientific course offered by the organization (Common Good Atlanta [CGA], n.d.). If you would like to get involved with expanding the scientific curriculum offered by CGA, please contact Andrea Pack.

References

Common Good Atlanta. (n.d.). Our Impact. Retrieved from http://www.commongoodatlanta.com/our-impact-1

Common Good Atlanta. (n.d.). Our Impact. Retrieved from http://www.commongoodatlanta.com/contact-2